Phage Therapy Offers Lifeline for Antimicrobial Resistance

SAN FRANCISCO — Bacteriophages, viruses that attack bacteria, may offer a life-saving alternative for multidrug-resistant bacterial infections that cannot be treated with available antibiotics, speakers said here.

Steffanie Strathdee, PhD, of the University of California San Diego (UCSD), told the dramatic tale of how she and a team of collaborators — largely working by trial and error — brought her husband back from the brink of death with phage therapy, an approach that is making a comeback in an era of increased antibiotic resistance.

“Phage therapy has had a number of false starts in the West since bacteriophages were first discovered in 1917. With the looming global threat of antimicrobial resistance and few promising antibiotics in the pipeline, our successful experience and that of others provides new momentum to evaluate phage therapy rigorously in clinical trials,” Strathdee told MedPage Today.

Strathdee, Associate Dean of Global Health Sciences and an expert on the health of people who use drugs, her husband, Thomas Patterson, PhD, a professor of psychiatry known for his HIV prevention work, and Robert “Chip” Schooley, MD, a renowned HIV expert and professor of medicine, all at UCSD, spoke at the closing plenary of IDWeek, jointly sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA), the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS).

Strathdee described how Patterson contracted an abdominal infection while on vacation in Egypt in late 2015. A clinic in Luxor diagnosed acute pancreatitis. His condition worsened and he was evacuated to Frankfurt, where a CT scan revealed “an abscess the size of a football in his abdomen” and tests identified highly resistant Acinetobacter baumannii that lost sensitivity even to colistin.

Patterson made it back to San Diego, where his condition deteriorated and he ended up on a ventilator. One of the drains placed into the pseudocyst slipped and “poured infected fluid into his abdomen, and he went immediately into septic shock,” Strathdee recalled. Although he seemed to be in coma, she asked if he wanted to live and he squeezed her hand, setting her off on a frantic hunt for alternatives.

Bacteriophages and Multidrug Resistance

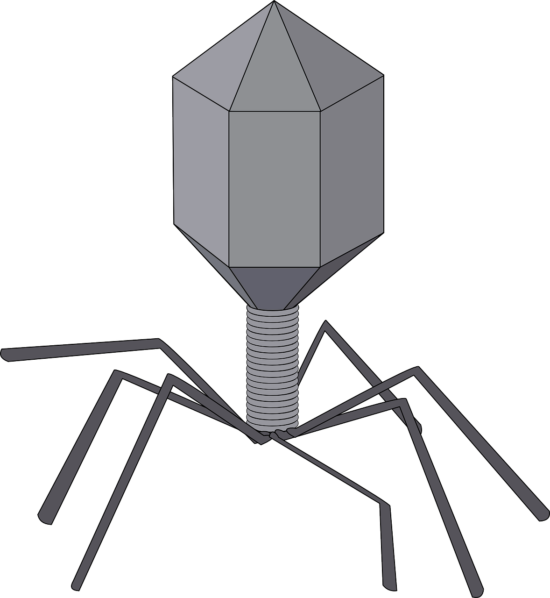

Searching the Internet, Strathdee came across bacteriophages, which she had learned about as a biology student. Bacteriophages penetrate and inject their DNA into bacteria, and the resulting viral replication leads to cell lysis.

Discovered more than 100 years ago, phage therapy has been widely used in Russia and Eastern Europe, but was largely eschewed as “pinko commie science” in the U.S., Strathdee said. After the advent of penicillin in the late 1920s, most western experts considered antibiotics the way to go.

Strathdee consulted with Schooley, a long-time colleague, and they agreed that after trying more than 20 antibiotics without much progress, there was little downside to trying phage therapy. But they would have to find right ones.

“The phages are extremely specific. This is nice from a microbiomic perspective. Unlike antibiotics, which are like dropping a bomb on an individual, you’re really treating the infection with lasers. But the lasers have to be well directed,” Schooley said.

Strathdee and Schooley contacted researchers across the U.S. and around the globe in search of phages that would be active against Patterson’s specific bacteria. At the same time, they worked with the FDA and university committees to fill out paperwork and bend the rules to authorize the use of the unapproved therapy.

The Center for Phage Technology at Texas A&M University and the Biological Defense Research Directorate of the U.S. Naval Medical Research Center both provided four-phage “cocktails” selected from phages collected from sewers and contributed by researchers worldwide. The first phage preparation was inserted directly into Patterson’s abdominal abscesses and the second was administered by IV infusions — a concern because laboratory phage preparations are contaminated with endotoxin, which can lead to septic shock.

“We really had no clue about what dose to use, what the frequency should be, whether we should give it into the cavities or parenterally, what we should expect in terms of the pharmacology of the phage, and what toxicities we should be concerned about,” Schooley said. “So it really was a complicated scenario, but we decided we wanted to jump on this organism as hard as we could.”

Source: MedPage Today

Healthy Patients