Guest blog: Why We Should Turn the Phage on Antibiotics

Although I’m an infectious disease epidemiologist and a professor with academic appointments in both the US and Canada, my firsthand experience with AMR was intensely personal. While we were on vacation to Egypt, a bacterium I used to steak on my petri plates back in the 1980’s – Acinetobacter baumannii– infected my husband and threatened to take his life. By the time he was transferred by air ambulance back to our home in California, his bacterial isolate had become pan-resistant. When I realized that my husband was dying, I took matters into my own hands. Although I was not an MD, I conducted a literature search and found a paper on bacteriophage therapy that rang a bell from my virology class decades ago.

Phages are the natural predators of bacteria, discovered over one hundred years ago by Felix d’Herelle, a self-taught French Canadian microbiologist. d’Herelle first used phages to treat a boy suffering from dysentery during an outbreak in Paris in 1919; the child was cured within 24 hours and subsequently, so were many others. Phage therapy became popular in the 1920’s and 30’s, especially in the former Soviet Union, where d’Herelle helped launch the first phage therapy center in what is now Tbilisi, Georgia. Meanwhile, after penicillin was introduced in 1942, phage therapy was largely abandoned in the West and was almost forgotten for decades outside of the Republic of Georgia and Poland.

When I proposed treating my husband with phage therapy in early 2016, most of the physicians treating him had never heard of it. Although phage therapy is standard of care in the former Soviet Union and parts of Eastern Europe, it is considered experimental by the Food and Drug Administration and similar European agencies. .

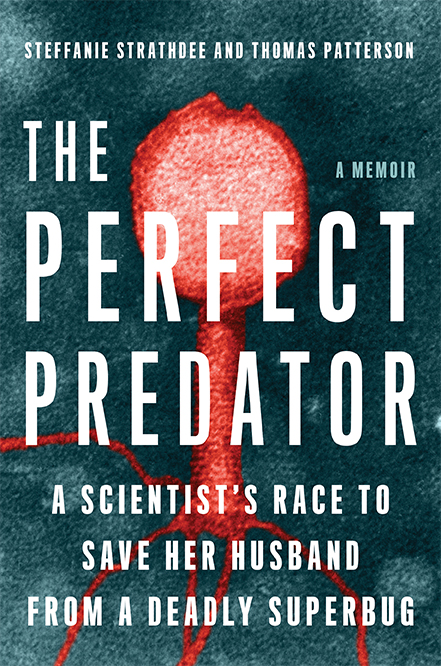

With the help of the internet, a global network of phage researcher across the US, Belgium, Switzerland, India and other countries, offered to undergo a phage hunt to find some to match to my husband’s bacterial isolate. Phage researchers from Texas A&M University turned their lab into a command center; within three weeks, they and researchers from the US Navy had each prepared a phage cocktail active against Tom’s strain that was purified enough to enable us to administer the phages intravenously. After the FDA gave emergency approval to administer phage for ‘compassionate use’, we injected one billion phages into my husband’s veins and his abdominal catheters every 2 hours. A few days later, he woke from a deep coma and began his long recovery. Our experience prompted us to write a book, The Perfect Predator (ThePerfectPredator.com), which we hope will encourage global awareness of AMR and phage therapy.

Soon after Tom’s case was presented at the Pasteur Institute’s 100th Anniversary of the discovery of bacteriophages in Paris in 2017 and again following publication of his case report, his doctors and I began receiving requests for phage therapy from all over the world. We were able to help some. Others sought treatment from Georgia, Poland or Belgium. Some died before phages could reach them. In response to these requests, my colleagues and I founded the non-profit Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH.ucsd.edu) at UC San Diego (UCSD) in 2018. Our goal is to conduct clinical trials on phage therapy while assisting patients with superbug infections obtain phage therapy if their infections are no longer responding to antibiotics.

Until recently, the pharmaceutical industry has viewed phage therapy with skepticism. However, a recent report of the first genetically modified phage to successfully treat a young teen with a multi-drug resistant Mycobacterium abscessus infection may change that, especially since this bacterium is a cousin to M.tuberculosis, the biggest bacterial killer in the world. Further, my husband’s case and others have shown that co-administration of phage and antibiotics can re-sensitize bacteria to some antibiotics. Further research and point-of-care diagnostics are needed to enable clinicians to rapidly identify and exploit these relationships. Looking ahead, the advent of genetically modified and synthetic phage that are more easily be patented may prompt a new era of antimicrobial treatment.

While phage therapy is unlikely to ever replace antibiotics, it is a promising alternative and/or adjunct that deserves to be rigorously evaluated in clinical trials. Given that few antibiotics are in the pipeline to address AMR, isn’t it high time to turn the phage?

By: Steffanie Strathdee, PhD

Associate Dean of Global Health Sciences,

Harold Simon Professor, University of California San Diego Department of Medicine

Co-Director, Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics

Author: The Perfect Predator: A Scientist’s Race to Save her Husband from a Deadly Superbug